I want to express my deepest gratitude to The Cripps Hall Trust for your generous sponsorship of my medical elective at Ekwendeni Mission Hospital in Malawi. The impact of this experience on both my personal and professional growth is difficult to adequately express. Undoubtedly, it was the highlight of my five years in medical school.

Ekwendeni Mission Hospital (EMH) in rural North Malawi is a beacon of hope, providing essential healthcare to the surrounding communities. Being part of this vital work has been immensely rewarding. I had the privilege of working alongside dedicated healthcare professionals who tirelessly serve the local population. Their compassion, resilience, and unwavering commitment were inspiring and set a valuable example for me as I embark on my medical career.

Operating with limited resources, EMH faces significant challenges. With only two doctors and six clinical officers, who undergo a brief three-year training course, the responsibility they shoulder is immense. Despite these limitations, EMH manages four wards, a theatre, an ultrasound room, and an outpatient department, along with various outreach programs.

However, resources are scarce. Routine blood tests are severely limited, and essential tests for kidney and liver functions are currently unavailable due to a lack of reagents. The ultrasound machine is outdated, and only one clinical officer is trained in its use and interpretation. Moreover, there is a shortage of basic medical supplies such as thermometers, blood pressure cuffs, and glucose monitors. The overcrowded wards often run out of dressings, gauze, fluids, and even essential items like mosquito nets.

A typical day at EMH began with a short walk from my basic hospital accommodation along a dusty mud road. Along the way, I interacted with local women selling “mandazi,” a donutlike snack that I often enjoyed. They greeted me warmly as I attempted to purchase “mandazi” in their local language, Tumbuka, with varying success. The day commenced with morning devotion at 7:00 a.m., although it frequently started later than scheduled due to the local concept of “Malawi time”. Devotion involved prayers, dancing, and gospel singing, setting a positive tone for the day ahead, reflecting a contrast to the more serious NHS handovers I was accustomed to. The 7:30 a.m. handover provided updates on new patients and medication availability, although shortages were common, especially with oral antibiotics. Throughout my time at EMH, I rotated through different wards, conducting patient reviews and assisting on ward rounds. In the maternity ward, for example, I conducted post-operative reviews with women who had undergone caesarean sections. Witnessing suboptimal pain management and dehydration, I worked to improve their postoperative pain using available medications and offered guidance to the ward staff on proper pain relief protocol. Throughout my time I encountered a variety of tropical diseases, including malaria, and learned invaluable lessons from the local clinicians on recognising and managing these conditions with limited resources.

I also spent several days in the theatre, assisting with various operations. The range of procedures was extensive, from the removal of testicular tumours to female sterilisation. Many patients presented with keloid scarring, a result of traditional healing methods involving pressing red-hot sticks into the skin. This meant that in addition to treating the initial illness, patients often required surgery to remove keloid scars. It was an enjoyable experience to support the doctors during these operations, as they typically worked without an assistant. Unlike the specialisation required in the NHS, EMH doctors handle a wide range of procedures. Due to limited resources and expertise, all surgeries at EMH are performed under local anaesthesia, even for operations involving large abdominal and pelvic incisions. It was difficult to witness at times, particularly when patients were left unnecessarily exposed and treated with less dignity than they would receive in the NHS.

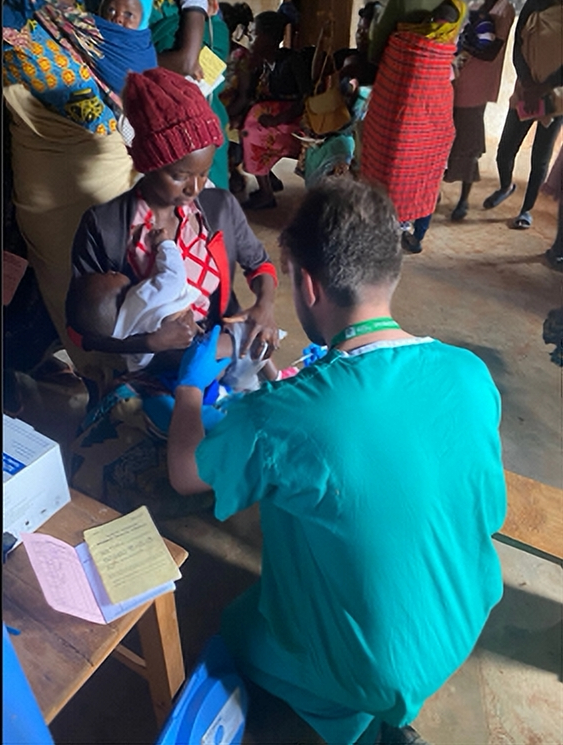

Participating in outreach clinics was another profound aspect of my experience. We travelled to remote communities in a 4×4 ambulance, carrying essential medical supplies such as vaccines, scales, blood-pressure cuffs, and tape measures. Our journeys often involved navigating muddy tracks and crossing rivers, enduring up to four hours of travel to reach isolated communities. The dedication of the local women was awe-inspiring. Many of them walked up to 40 kilometres, often barefoot and throughout the night, just to attend the clinic. Arriving at these clinics, we were met with over 100 women patiently sat on the floor awaiting our assistance. Before commencing the clinics, we engaged in singing and dancing conducted in Tumbuka. The songs revolved around various healthcare topics, including HIV, cholera, and family planning. Witnessing the unfiltered joy and laughter of the community members during these moments was a profoundly moving experience. It became apparent that my presence as a white individual, or “muzungu” as I was called, was unfamiliar to many of the locals, who hadn’t encountered someone like me for years. To bridge this gap, I tried to learn basic Tumbuka phrases. It helped establish trust, facilitate communication, and create a connection with the community members.

Inside the clinic, each room served a distinct purpose. One room was dedicated to childhood vaccinations, another focused on monitoring the health of pregnant women, and a separate room facilitated HIV testing for couples planning a pregnancy. As the sole medical student present, I often found myself looked upon for guidance by the staff when uncertainties arose. One memorable incident occurred while I was assisting with vaccinations. A healthcare worker sought my advice on a child whose head had been abnormally enlarging for several weeks. Upon examination, it was evident that the baby suffered from hydrocephalus, a condition characterised by an accumulation of excess fluid inside the skull. In this case, the pressure caused by the accumulation of fluid meant the child was extremely unwell, exhibiting what is known as sunset-eyes. Recognising the severity, I advised against administering the vaccines and instead arranged for the mother and child to be transported to Mzuzu Central, the main hospital serving the northern region of Malawi. The hope was that the hospital could perform a life-saving procedure by inserting a stent. Such experiences were unlike anything I had witnessed during my time in the NHS. Participating in these outreach clinics was a profound privilege and deepened my understanding of the immense challenges faced by rural communities in accessing healthcare.

Additionally, I had the privilege of spending a day with a community nurse named Maria, who revealed that she was HIV positive and dedicated herself to working with approximately 300 HIV-positive individuals in the local community. These individuals were often outcasts and faced difficulties accessing healthcare, suffering from the medical consequences of AIDS. Spending time with Maria allowed me to visit various patients who lacked access to medical support. Each patient was incredibly hospitable and invited me into their home. I was humbled by how little these patients had, having sold most of their belongings to pay for medical treatment. These patients faced conditions such as malnutrition, pressure ulcers, and vulval cancer—conditions directly related to their HIV status. It was humbling to be involved in providing guidance on pain management, wound care using simple methods like saltwater, and ensuring suitable nutrition with the limited food available to them.

Outside of my hospital duties, I actively immersed myself into the local community through my involvement with Tafika, a youth charity names after the Tumbuka phrase “we have arrived”. Joining Tafika allowed me to forge meaningful connections and dedicate my weekends to supporting community initiatives. One notable project involved Tafika sponsoring young boys from neighbouring villages to participate in a highly anticipated football tournament, drawing crowds exceeding 3000 people. During half-time, we organised a local band to perform songs with important public health messages related to the ongoing cholera outbreak. Through my close ties with Tafika, I was fortunate to be welcomed into the homes of local villagers, gaining invaluable insights into their daily lives. Their exceptional hospitality often resulted in multiple lunch invitations in a single day. Without wanting to offend by declining, I ended up accepting all invitations and feeling rather full! Additionally, I participated in local funeral traditions where I joined hundreds of others in camping outside the bereaved families’ homes, sharing stories and warmth around campfires. I also enjoyed exploring the local villages during my runs, often accompanied by young children and friendly local dogs.

I want to emphasise my gratitude to The Cripps Hall Trust for making my journey to Malawi possible. Your sponsorship covered my travel expenses, accommodation, and daily needs during my volunteering period. Additionally, thanks to your support, I was able to identify and provide EMH with some of the medical supplies they needed the most. Your generosity and belief in the importance of medical education has empowered me to make a meaningful contribution to underserved populations. Your support’s impact extends beyond my personal growth and will have a lasting effect on the countless individuals benefiting from healthcare services at Ekwendeni Mission Hospital.

Inspired by my experiences in Malawi, I am committed to completing an Iron Man in 2024 to raise funds for Tafika. Additionally, upon completing my two-year doctor training, I intend to return to EMH for an extended period, providing additional support and facilitating staff training. With increased medical knowledge, I will be better equipped to contribute effectively.

Once again, I extend my sincerest gratitude to The Cripps Hall Trust.

Samuel Quick,

5th year Medical Student, The University of Nottingham.

(June 2023)